By now, our regular readers know that here at EBL, we value systematic reviews above other forms of evidence. That’s because these reviews collect all of the available evidence on a given topic to provide a summary of what we know and an assessment of the data quality. In short, they’re the best way to find a definitive answer about what does and doesn’t work.

By now, our regular readers know that here at EBL, we value systematic reviews above other forms of evidence. That’s because these reviews collect all of the available evidence on a given topic to provide a summary of what we know and an assessment of the data quality. In short, they’re the best way to find a definitive answer about what does and doesn’t work.

An evidence-based birthday

An update on barefoot running

Here on EBL, we’ve written before about the trend of barefoot running and minimalist running shoes. Last week, the American College of Sports Medicine held its annual conference. There, researchers presented five separate studies on the benefits of running barefoot or with minimal footwear. [Read more…]

Here on EBL, we’ve written before about the trend of barefoot running and minimalist running shoes. Last week, the American College of Sports Medicine held its annual conference. There, researchers presented five separate studies on the benefits of running barefoot or with minimal footwear. [Read more…]

The real evidence on prophylactic mastectomies

When actress Angelina Jolie revealed last week in the New York Times that she had a double mastectomy to prevent breast cancer, media outlets across the country interviewed doctors, breast cancer patients, and generally added their two cents to the discussion about whether this type of surgery is worthwhile. [Read more…]

When actress Angelina Jolie revealed last week in the New York Times that she had a double mastectomy to prevent breast cancer, media outlets across the country interviewed doctors, breast cancer patients, and generally added their two cents to the discussion about whether this type of surgery is worthwhile. [Read more…]

In the media: Evidence-based mental health therapy?

The New York Times’ Well Blog has a fascinating post this week on why mental health therapists do not consistently use evidence-based techniques in treating their patients. [Read more…]

The latest evidence on Vitamin D

Keeping track of the latest evidence on which vitamin supplements to take can be confusing. Although new information is available regularly, mainstream media outlets don’t always report the full story, which can result in conflicting reports.

Keeping track of the latest evidence on which vitamin supplements to take can be confusing. Although new information is available regularly, mainstream media outlets don’t always report the full story, which can result in conflicting reports.

There is new, clear evidence this month: The U.S. Preventative Services task force is recommending that healthy, postmenopausal women should not take Vitamin D and calcium supplements to prevent fractures.

The task force – an independent panel of medical experts – reviewed more than one hundred medical studies before making their recommendation. It found insufficient evidence that taking vitamin D and calcium actually helps prevents fractures, and found a small risk of increased kidney stones for people who did take the supplements.

The task force’s recommendation does not apply to people suffering from osteoporosis or vitamin D deficiencies, or those living in skilled nursing facilities.

Cornell nutritionist Patsy Brannon has weighed in on the national debate over vitamin D supplements. Brannon was on the Institute of Medicine panel. While the panel recommended increasing the daily intake of vitamin D, it did not find that a deficiency is linked to chronic conditions such as cancer, diabetes and heart disease.

“The evidence available is inconsistent, with some studies demonstrating this association while others show no association, and still others show evidence of adverse effects with high blood levels of vitamin D,” Brannon told the Cornell Chronicle. Although we can’t conclude whether low vitamin D is associated with chronic disease, the evidence is clear that these vitamin supplements do not prevent fractures.

Debunking weight-loss myths

As our nation continues to struggle with an obesity epidemic and individuals work to lose weight with diet and exercises programs, a group of researchers from University of Alabama at Birmingham want to make sure we know what not to do.

As our nation continues to struggle with an obesity epidemic and individuals work to lose weight with diet and exercises programs, a group of researchers from University of Alabama at Birmingham want to make sure we know what not to do.

In an article published earlier this year in the New England Journal of Medicine, obesity researchers reviewed the evidence about losing weight to identify what we really know about the best ways to lose weight.

They identified 7 commons myths about losing weight which are not true:

1. Small changes in diet and exercise will create big, long-term weight changes.

2. Setting realistic goals for weight loss is important to prevent frustration.

3. Rapid weight-loss is less successful over the long-term than gradual weight loss.

4. Patients who want to lose weight must be “mentally ready.”

5. Physical education classes play an important role in preventing childhood obesity.

6. Breastfeeding protects babies against obesity later.

7. Sexual activity is a good way to burn calories.

The review also identified some common perceptions about losing weight that are, in fact, supported by strong evidence:

- Genetics play a role in weight loss, but that factor is not insurmountable.

- Exercise helps people maintain their weight.

- Patients lose more weight on programs that provide meals.

- Some prescription drugs help with weight loss and maintenance.

- Weight-loss surgery is an effective way to maintain long-term weight loss and reduce mortality in appropriate patients.

The study also listed some ideas about weight loss that are still not proven or disproven by the current available evidence. For example, we don’t actually know whether eating breakfast regularly aids in weight loss, or whether people who snack often are more likely to gain weight.

In general, the medical community and researchers have praised the study for providing an accurate picture of what we know – and what we don’t – about losing weight. The idea going forward is that researchers should continue to develop new evidence on the most effective methods for losing weight.

The case for taking aspirin

It’s always a pleasure to see a mainstream media outlet providing the big picture on medical therapies. So I was fascinated by a recent opinion piece in the New York Times which called for the increased use of aspirin.

It’s always a pleasure to see a mainstream media outlet providing the big picture on medical therapies. So I was fascinated by a recent opinion piece in the New York Times which called for the increased use of aspirin.

In the article, cancer-researcher Dr. David Agus makes a clear case of the health benefits of aspirin. For years, the evidence has clearly established that aspirin reduced the risk of cardiovascular disease. In fact, he points out, the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force – an independent panel of health care experts – recommended aspirin for people up to 80 years old to prevent heart disease.

Now there is a growing body of solid evidence that aspirin also helps reduce the risk of cancer. Several major systematic reviews found that people who take an aspirin a day over the period of several years reduce their risk of developing cancer.

One major systematic review published by British researchers pulled together data on more than 77,000 patients from 51 separate clinical trials. It found some striking results: people who took aspirin daily were 15 percent less likely to die from cancer compared with those who didn’t take aspirin. They also had a 38 percent reduction in the risk of colorectal and gastrointestinal cancer. And for aspirin-takers who did get cancer, it was 38 percent less likely to spread to other parts of their bodies.

Other reviews have found that aspirin use not only reduces the risk of colorectal and gastrointestinal cancer but also decreases distant metastasis, the spreading of cancer to new regions of the body.

The take-home message: While people have been using aspirin for thousands of years, it was likely to be providing more health benefits than were ever realized.

The evidence shows preschool matters!

We have heard educators and politicians alike tout the virtues of early childhood education, and how it prepares kids for a lifetime of learning. With one of my own children in preschool and another one headed there shortly, I’m always interested in the evidence on this stage learning. Do activities like playing with blocks and paints, sitting through circle time and learning to share really impact a child for the rest of his life?

We have heard educators and politicians alike tout the virtues of early childhood education, and how it prepares kids for a lifetime of learning. With one of my own children in preschool and another one headed there shortly, I’m always interested in the evidence on this stage learning. Do activities like playing with blocks and paints, sitting through circle time and learning to share really impact a child for the rest of his life?

So I was fascinated to follow a series of reports on National Public Radio that detail some interesting evidence about preschool programs. While these reports didn’t include a systematic review, they did include several different longitudinal studies that make an interesting case about the importance of preschool.

On the show This American Life, host Ira Glass talks with a range of experts – a journalist, an Nobel-prize winning economist and a pediatrician – about the evidence on what researchers call “non-cognitive skills” like self-discipline, curiosity and paying attention.

One of the leading experts in this field is an economist at the University of Chicago named James Heckman. His work has found that these soft skills are essential in succeeding in school, securing a good job, and even building a successful marriage. Heckman found that children learn these skills in preschool.

One well-known longitudinal study followed a group of low-income 3- and 4-year-olds in Ypsilanti, MichiganThese children were randomly assigned to attend preschool five days a week, or not attend any preschool. After preschool, all of the children went to the Ypsilanti public school system.

The study found that children who attend preschool were more successful adults. They were half as likely to be arrested and earned 50 percent more in salary. Girls who attended preschool were 50 percent more likely to have a savings account and 20 percent more likely to have a car.

Another similar project conducted in North Carolina found that comparable results: Individuals who had attended preschool as children were four times more likely to have earned college degrees, less likely to use public assistance, and more likely to delay child-bearing.

There is more evidence too. NPR’s Planet Money aired a show earlier this year demonstrating further evidence about the benefits of preschool. And researchers at the University of Texas in Austin found that preschool reduces the inequalities in early academic achievement.

The take-home message seems to be: Preschool matters!

The evidence on arsenic and rice

The magazine Consumer Reports released a study last month that revealed low levels of arsenic – a chemical element that is toxic when consumed in higher doses – in rice and rice products grown across the world.

The magazine Consumer Reports released a study last month that revealed low levels of arsenic – a chemical element that is toxic when consumed in higher doses – in rice and rice products grown across the world.

The study tested 223 types of rice and rice products – such as rice-based cereals and rice milk – purchased in the United States in April, May and August of this year. It found arsenic in every product it tested, and dangerous levels of inorganic arsenic in dozens of products. Consumer Reports the story points out that their study is “a spot check of the market and “too limited to offer general conclusions about arsenic levels in specific brands within/across rice product categories.” Nevertheless, their article raises some surprising questions about toxins in our food supply.

Following the Consumer Reports study, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration released some preliminary results of a long-term study on arsenic levels in our food supply. Their study found levels of arsenic in rice similar to the Consumer Reports study.

So, what’s a rice-lover to do? Consumer Reports recommends limiting consumption of rice and rice products, while the FDA is not recommending any limits on rice consumption.

Since the FDA and Consumers Reports found the same level of arsenic in food, the question in my mind is: Exactly how dangerous is low-level exposure to arsenic? A search of systematic reviews yielded some interesting results.

- One meta-analysis found consuming arsenic in drinking water is associated with a higher risk of lung cancer.

- Another analysis found chronic arsenic exposure can lead to mental retardation and developmental disabilities such as physical, cognitive, psychological, sensory and speech impairments – although in higher levels that measured in the rice products tested by Consumer Reports and the FDA.

- Other analyses found inconclusive results on the relationship between arsenic exposure and diabetes and arsenic exposure and cardiovascular disease – although both of these reviews identified limitations in the study methodology and called for additional research.

My plan is to think more carefully about the rice products my family consumes. I’m not going to throw out the brown rice in my pantry, and we will still enjoy stir fry and sushi on a regular basis. But I certainly plan to steer way from rice cereals and other rice products at the grocery store.

The science of political campaigns, Part 2

Next month, President Barack Obama and Republican Presidential Candidate Mitt Romney will face off on national television on four separate occasions to share their ideas for governing America and explain why voters should chose them.

Next month, President Barack Obama and Republican Presidential Candidate Mitt Romney will face off on national television on four separate occasions to share their ideas for governing America and explain why voters should chose them.

While it’s not clear how many Americans make their voting decisions based on the debates, we do know they are an important part of the campaign. So I was thrilled to find some evidence on how to consider the candidates responses critically.

Todd Rogers, a behavioral psychologist at Harvard University, is among a growing group of researchers applying social science to issues effecting political campaigns. (We’ve written about his work on get-out-the-vote phone calls.) He wanted to address the issue of how candidates respond when get asked a question that they don’t want to answer – and whether the public notices when politicians dodge a question by talking about a different topic instead.

Rogers and his colleague Michael Norton, an associate professor at the Harvard Business School, designed a study to determine under what conditions people can get away with dodging a question, and under what conditions listeners can detect what’s happening.

In their study, published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology, they recorded a speaker answering a question about universal healthcare. Then they paired that answer with three separate questions: the correction question about health care, one about illegal drug use and another about terrorism. They showed the three question-and-answer pairings to separate groups of people and asked them to rate the truthfulness of the speaker.

Their research found that when the question and answer sounded somewhat similar – such as in the case where the speaker was asked about drug use but responded about healthcare – the audience rate the speaker as trustworthy. (In fact, most of the people who head the answer about illegal drug use couldn’t even remember the question.) But when the answer was very clearly addressing a different topic – such as when the speaker was asked about health care but responded about terrorism – the audience detected the dodge.

In another part of the study, Rogers and Norton used the same questions and answers, but posted the question on the screen in for some viewers. They found viewers who saw the question posted on the screen while the speaker answered were more than twice as likely to detect a dodge, even in subtle cases.

Rogers advocates for posting the questions on the screen during the presidential candidates debates, although he concedes it’s unlikely to happen this year.

You can hear an interview with Rogers and learn about other research on political campaigning in last week’s episode of NPR’s Science Friday.

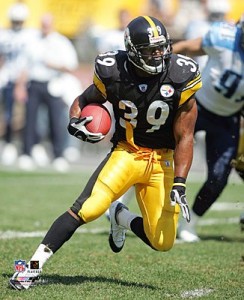

Football frets: The evidence on repetitive head injuries

With football season underway, many Americans are spending their weekends cheering on their favorite teams at stadiums and tuning in to watch televised games. Personally, I enjoy following my college football team. But I always feel a sense of dread when a player takes an especially hard hit.

With football season underway, many Americans are spending their weekends cheering on their favorite teams at stadiums and tuning in to watch televised games. Personally, I enjoy following my college football team. But I always feel a sense of dread when a player takes an especially hard hit.

It turns out, those repeated hits add up to some real neurological problems for football players.

A study published this week in the journal Neurology followed nearly 3,500 football players who played at least five seasons in the N.F.L. from 1959 to 1988.

Over the course of the study, 334 of the players died. When researchers from the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health reviewed their death certificates, they found Alzheimer’s disease was an factor in seven of the deaths and Lou Gehrig’s disease was a factor in seven others. These rates are more than three times what you would expect to see in the normal population.

This new study is part of a growing body of research on the neurological repercussions of repeated head injuries. Another study published earlier this year found repetitive head impacts over the course of a single season may negatively impact learning in some collegiate athletes.

And a center at the Boston University School of Medicine has documented evidence of a condition called Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, or CTW, a progressive degenerative disease of the brain found in people with a history of repetitive brain trauma.

The N.F.L. is investing in more research. This week, the organization donated $30 million to the National Institutes of Health for research on the connection between brain injuries and long-term disorders. That’s a good thing, because this is one topic we need more evidence on.

Slimming it down? New evidence on low-calorie diets

Over the past few years, you may have heard the buzz about the potential for a low-calorie diet to prolong life and prevent chronic medical conditions like heart disease and cancer.

Over the past few years, you may have heard the buzz about the potential for a low-calorie diet to prolong life and prevent chronic medical conditions like heart disease and cancer.

While the concept of restricting calories has been around for decades, a longitudinal study of monkeys published in 2009 seemed to provide definitive evidence that eating less was good for you. The study by researchers at the University of Wisconsin found a diet of moderate caloric restrictions over 20 years lowered the incidence of aging-related deaths and reduced the incidence of diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and brain atrophy.

But last week, a new longitudinal study of different species of monkey raised questions about the idea of restricting calories to improve health. The study included 121 monkeys split into two groups. The experimental group was fed 30 percent fewer calories than the control group.

In the study published last week, which was sponsored by the National Institute on Aging, the monkeys on restricted diets did not live any longer than those with normal diets. Rates of cancer and heart disease were the same for monkeys on restricted diets and normal diets. While some groups of monkeys on restricted diets had lower levels of cholesterol, blood sugar and triglycerides, they still did not live longer than the monkeys who ate normally.

The study is interesting from a health perspective because it raises questions about the notion of restricting calories to improve health. But it’s also a prime example of why it’s important to collect data from more than one study.

“This shows the importance of replication in science,” Steven Austad, interim director of the Barshop Institute for Longevity and Aging Studies at the University of Texas Health Science Center, told the New York Times. Austad, who was not involved in either study, also explained that the first study was not as conclusive as portrayed in the media.

The take home message: It’s important to collect evidence from multiple studies before drawing conclusions, even when the data seems extremely convincing.