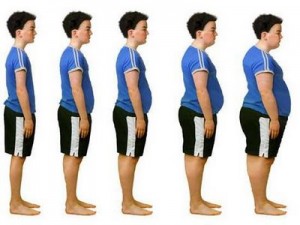

There are some problems we can’t do much about — hurricaines and earthquakes, for example. But a vast amount of things that make life tough — and sometimes miserable — relate to the choices human beings make and the way we behave. For this reason, a whole science of behavior change has grown up, focusing both on theoretical models and empirical studies of how to change damaging human behaviors, ranging from smoking, to crime, to overeating, to taking excessive risks.

A very helpful new article reviews models to promote positive behavior change that are highly relevant to people designing or implementing interventions. The authors note that getting individuals to make lasting changes in problem behaviors is no easy matter. They synthesize various models of behavior change “to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how educators can promote behavior change among their clientele.”

The authors apply their framework to the issue of financial management. Very interesting reading, available here.

(While you’re at it, take a look at other issues of this free on-line journal, called the The Forum for Family and Consumer Issues, published by North Carolina State University Extension — many interesting articles related to program development and evaluation.)