I will never forget the moment, even though it was years ago. My wife and I were chatting with the parents of one of our daughter’s friends, and the topic of a recent sleep-over came up. They told us that the kids – all young teens – had camped out behind their house, which surprised us. But our jaws progressively dropped as this couple went on to say how they had provided beer to the kids. When we expressed dismay, they responded along the lines of “Well, they’re going to do it anyway.” This seemed to us wrong to the core, but it indicates the dilemmas parents face in trying to control teen drinking behavior.

There is a mountain of scientific data about the dangers of teen alcohol use. Perhaps most frightening is that teenage drinking predicts alcohol abuse as an adult. Adolescent alcohol use is also related to driving accidents and fatalities, poor school performance, and engaging in other types of risky behaviors. In fact, there’s so much data on the negatives of teen alcohol consumption that EBL won’t even waste your time with a review.

But what’s a parent to do? That’s where information from a recent systematic review breaks new ground (for information about systematic reviews and why they’re so good, see here).

In their article, Siobhan Ryan, Anthony Jorn, and Dan Lubman conducted a state-of-the-art systematic review about what parenting strategies are associated with adolescent alcohol consumption. Two positive outcomes were examined: delayed onset of teen drinking (the later the better) and levels of alcohol consumption in adolescence. The review only looked at longitudinal studies, where data on parenting practices were collected early in adolescence and data on drinking at a later time point. These are very strong designs. Further, they carried out sophisticated statistical analyses to combine the results of studies.

Let’s come back to our question: What’s a parent to do? It turns out that there are a number of parenting strategies that work to reduce teen drinking. Four of the most important of these are:

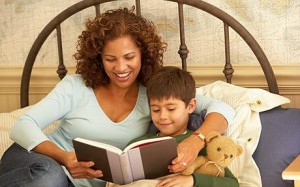

- Parental modeling – and specifically children learning about alcohol by observing the parents’ responsible drinking behavior

- Parental monitoring – the degree to which parents know where there children are and who they are with

- Parent – child relationship quality – the level of warmth and affection in the relationship

- Limiting availability of alcohol – not providing alcoholic beverages to the child

I was particularly glad to see that last one, because every once in a while I wonder if I was wrong to criticize those parents who created a beer party for young teens. It turns out I was right. An editorial accompanying the review article puts this issue succinctly:

Many parents consider that this is the best way to prevent negative alcohol outcomes in their children, i.e. by allowing drinking at home and directly supplying them with small amounts of alcohol when they go out to parties. In fact some parents go out of their way to inoculate their children with alcohol, sometimes before puberty, in order to break down any sense of alcohol being a taboo. This normalization of drinking alcohol is aimed at lessening the “big deal” of adolescent initiation rites involving alcohol. However, the evidence points in the opposite direction, that normalization of alcohol increases the risk of harm.

By being a good role model, monitoring one’s children carefully, and maintaining warm relationships, parents can make inroads into this very thorny problem, and perhaps keep their kids sober longer.