As the Internet and social media continue to transform our society, today’s youth are growing up in unchartered waters. For young people who confront problems like depression, the Internet is a particularly tricky issue to navigate.

As the Internet and social media continue to transform our society, today’s youth are growing up in unchartered waters. For young people who confront problems like depression, the Internet is a particularly tricky issue to navigate.

Does exercise help alleviate depression?

If I come home in a bad mood, my husband usually suggests I head out for a run or over to the pool for a swim. That’s because he knows that exercise helps to improve my frame of mind. But does it also help improve the symptoms for people suffering from clinical depression? [Read more…]

If I come home in a bad mood, my husband usually suggests I head out for a run or over to the pool for a swim. That’s because he knows that exercise helps to improve my frame of mind. But does it also help improve the symptoms for people suffering from clinical depression? [Read more…]

The evidence on schools and risky behavior

Evidence check: New medical treatments often lacking

It’s human nature to assume that new often means better. But in the case of medical treatments, that’s not always the case. In a new systematic review published in the Mayo Clinic Proceedings, researchers reviewed 10 years of previous issues of the New England Journal of Medicine to identify the benefits of various medical practices which were described.

It’s human nature to assume that new often means better. But in the case of medical treatments, that’s not always the case. In a new systematic review published in the Mayo Clinic Proceedings, researchers reviewed 10 years of previous issues of the New England Journal of Medicine to identify the benefits of various medical practices which were described.

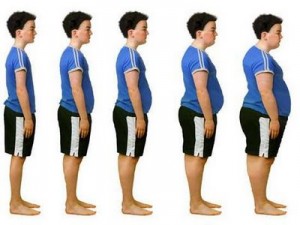

Is obesity really a disease?

Last month, the American Medical Association classified obesity as a disease in its own right for the first time. (Previously, it had been categorized as a symptom or risk factor.) There is plenty of evidence that shows people who are obese are more likely to develop diabetes and cardiovascular disease. But does that make obesity a disease in its own right? What about being overweight, but not obese?

Last month, the American Medical Association classified obesity as a disease in its own right for the first time. (Previously, it had been categorized as a symptom or risk factor.) There is plenty of evidence that shows people who are obese are more likely to develop diabetes and cardiovascular disease. But does that make obesity a disease in its own right? What about being overweight, but not obese?

Gaps in evidence: Gun violence in America

News stories about the problem of gun violence in America have dominated media outlets across the country over the past year. The tragic school shooting in Newtown, Connecticut continues to fuel an on-going debate about the laws surrounding violence and safety in our society. It’s a sensitive subject, and many people across the nation hold opposing viewpoints about what should be done. But one thing is clear: gun violence is a critical public health problem.

News stories about the problem of gun violence in America have dominated media outlets across the country over the past year. The tragic school shooting in Newtown, Connecticut continues to fuel an on-going debate about the laws surrounding violence and safety in our society. It’s a sensitive subject, and many people across the nation hold opposing viewpoints about what should be done. But one thing is clear: gun violence is a critical public health problem.

Proven methods to quit smoking

One in five deaths in the U.S. can be credited to tobacco, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control – a statistic that makes it clear: Smoking is a huge health problem. [Read more…]

One in five deaths in the U.S. can be credited to tobacco, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control – a statistic that makes it clear: Smoking is a huge health problem. [Read more…]

Evaluating programs to promote teen sexual health

Teenagers and young adults represent only 25 percent of the sexually active population in the U.S., but they acquire nearly half of all new sexually transmitted infections, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. [Read more…]

Teenagers and young adults represent only 25 percent of the sexually active population in the U.S., but they acquire nearly half of all new sexually transmitted infections, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. [Read more…]

Debunking weight-loss myths

As our nation continues to struggle with an obesity epidemic and individuals work to lose weight with diet and exercises programs, a group of researchers from University of Alabama at Birmingham want to make sure we know what not to do.

As our nation continues to struggle with an obesity epidemic and individuals work to lose weight with diet and exercises programs, a group of researchers from University of Alabama at Birmingham want to make sure we know what not to do.

In an article published earlier this year in the New England Journal of Medicine, obesity researchers reviewed the evidence about losing weight to identify what we really know about the best ways to lose weight.

They identified 7 commons myths about losing weight which are not true:

1. Small changes in diet and exercise will create big, long-term weight changes.

2. Setting realistic goals for weight loss is important to prevent frustration.

3. Rapid weight-loss is less successful over the long-term than gradual weight loss.

4. Patients who want to lose weight must be “mentally ready.”

5. Physical education classes play an important role in preventing childhood obesity.

6. Breastfeeding protects babies against obesity later.

7. Sexual activity is a good way to burn calories.

The review also identified some common perceptions about losing weight that are, in fact, supported by strong evidence:

- Genetics play a role in weight loss, but that factor is not insurmountable.

- Exercise helps people maintain their weight.

- Patients lose more weight on programs that provide meals.

- Some prescription drugs help with weight loss and maintenance.

- Weight-loss surgery is an effective way to maintain long-term weight loss and reduce mortality in appropriate patients.

The study also listed some ideas about weight loss that are still not proven or disproven by the current available evidence. For example, we don’t actually know whether eating breakfast regularly aids in weight loss, or whether people who snack often are more likely to gain weight.

In general, the medical community and researchers have praised the study for providing an accurate picture of what we know – and what we don’t – about losing weight. The idea going forward is that researchers should continue to develop new evidence on the most effective methods for losing weight.

The serious effects of physical discipline

There are many factors that influence how parents discipline their children: parents’ own upbringing, family customs and stress levels all factor in. But there is clear evidence that some forms of discipline – specifically physical punishment – have negative effects on children throughout their lives.

A new systematic review reveals a body of evidence demonstrating physical punishment may increase the chances of antisocial behavior and aggression, depression, anxiety, drug abuse and psychological problems later in life.

The review is especially interesting because it discusses intervention programs designed to reduce physical punishment and child abuse. It included a trial of one intervention that taught parents to reduce their use of physical punishment, which led to less difficult behavior by their children.

Another such program – called Triple P – originated in Australia was tested in a study funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. The program uses a broad range of strategies to address physical abuse including consultations with parents, public seminars and public service announcements on local media. It led to significantly positive results that are encouraging if replicated in other areas of the U.S. Counties that implemented the program had lower rates of substantiated child abuse cases, fewer instances of children removed from their homes and reductions in hospitalizations and emergency room visits for child injuries.

John Eckenrode, professor of human development and director of Cornell’s Bronfenbrenner Center for Translational Research, is an expert in child abuse and maltreatment. He’s written a chapter about preventing child abuse in the book Violence against women and children, published by the American Psychological Association.

“We know that there are tested and effective ways to support parents so that they can better provide a safe and supportive environment for their children without resorting to physical punishment,” he said. “But we must get the word out, provide those who interact with parents such as teachers and physicians with the tools they need to promote positive parenting strategies, and provide resources to states and localities to scale-up effective programs.”

The take-home message: Physical punishment and child abuse are serious problems that have life-long effects. But there is a growing body of evidence that intervention programs can help guide parents to other methods of discipline.

The evidence on preventing weight gain

We’ve all heard extensively about the obesity epidemic that impacts millions of Americans, leading to heart disease, stroke and cancer, among other problems. And, of course, it’s the time of year when many of us make new year’s resolutions to lose weight, exercise more and generally improve our health. But what methods work the best?

We’ve all heard extensively about the obesity epidemic that impacts millions of Americans, leading to heart disease, stroke and cancer, among other problems. And, of course, it’s the time of year when many of us make new year’s resolutions to lose weight, exercise more and generally improve our health. But what methods work the best?

To answer that question, I dug up a systematic review of lifestyle changes to help prevent weight gain in people who were normal weight, overweight and obese. The researchers looked at 40 studies on a wide array of interventions including low-calorie diets, Weight Watchers, meal replacement, behavior therapy by trained nutritionists, low-fat diets, exercise programs and others.

The conclusion? There are many effective ways to lose weight and prevent weight gain. Eight interventions yielded significant improvement in weight control . These included low-fat diets with and without meal replacements, low calorie diets, Weight Watchers, and diets with behavior therapy.

The review did not find enough evidence to support lifestyle interventions to prevent weight gain in normal-weight adults. It called for better study design as well as improved reporting of participant characteristics and outcomes in weight loss studies.”

The take-home message here: To lose or prevent gaining weight, your best move is to do something. Whether it’s diet, exercise, behavior therapy, or a combination of the three, it’s likely to yield results.