On EBL, we’ve talked a lot about research evidence on problems affecting adolescents, from alcohol use, to video games, to social networking, to sex (I can hear teens who read this starting to hum the tune to “These Are a Few of My Favorite Things”…).

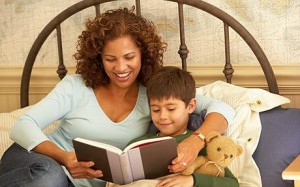

One might ask: Okay, what about the positive side? We’re glad to say that there’s very encouraging news about a program that really works.

One of the most popular and extensive youth programs in the United States is the 4-H program. There are over 6,500,000 members in the U. S. The 4-H program offers activities for kids from 5-19 who are organized in 90,000 4-H clubs. Throughout its history, 4-H has promoted leadership skills, good citizenship, and life skills development. In recent years, it has branched into health promotion programs (like obesity prevention and fostering physical activity) and science, engineering, and technology (“SET”) programming.

All this sounds great, right? But as EBL readers know, we look for the evidence. And now we have it, thanks to the ground-breaking work of Prof. Richard Lerner of Tufts university, one of the country’s leading experts on youth development. Lerner and colleagues expected that the mentoring from adult leaders and the structured learning that goes on in clubs might lead to number of desireable outcomes for children. This led them to do a longitudinal, controlled evaluation of the impact of being a 4-H member. Beginning in 2002, they have surveyed oaver 6,400 teens across the U. S.

The researchers have issued a major new report, looking at the findings on youth outcomes over nearly a decade. To really dig into the results, you should read the very accessible report. Among the many findings, according to the report summary, is that 4-H participants:

- Have higher educational achievement and motivation for future education

- Are more civically active and make more civic contributions to their communities

- Are less likely to have sexual intercourse by Grade 10

- Are 56% more likely to spend more hours exercising or being physically active

- Have had significantly lower drug, alcohol and cigarette use than their peers

- Report better grades, higher levels of academic competence, and an elevated level of engagement at school,

- Are nearly two times more likely to plan to go to college

- Are more likely to pursue future courses or a career in science, engineering, or computer technology

All in all, very impressive findings. So let’s join in the 4-H pledge (can you find the four “H”s?):

I pledge my head to clearer thinking,

my heart to greater loyalty,

my hands to larger service

and my health to better living,

for my club, my community, my country, and my world.

A pretty good approach to living, and one that seems to work for millions of children and teens!