With my second child due any day now, I admit I’ve got babies on the brain at the moment. If there’s one thing the evidence clearly shows, it’s that breastfeeding is good for both moms and babies.

With my second child due any day now, I admit I’ve got babies on the brain at the moment. If there’s one thing the evidence clearly shows, it’s that breastfeeding is good for both moms and babies.

Review after review shows that breastfeeding protects against asthma, childhood obesity, ear infections, respiratory illness and more. It helps mothers avoid breast and ovarian cancer, and leads to quicker weight-loss after having a baby. (You can find a good review of that evidence and more from the U.S. Surgeon General’s office.)

In addition, there are economic benefits to families. Formula is expensive!

But across the U.S., less than half of women continue breastfeeding after six months. And among some populations, such as African-American women, those rates are much lower.

Luckily, there is also good evidence that educational programs are effective in promoting breastfeeding among new mothers. The best method seems to be in-person training –whether with a nurse at the hospital, at pediatrician’s offices or in a support group for new mothers all proved effective in increasing the number of infants who are breastfed at three months of age.

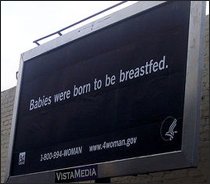

There are other interventions that help as well. In fact, the U.S. government has deemed this is such an important issue that the Centers for Disease Control has published a list of evidence-based guidelines to breastfeeding interventions. Among the recommendations are providing support in the workplace for breastfeeding women and creating media campaigns to improve attitudes toward breastfeeding.

I feel extremely lucky that the hospital where I plan to deliver and our pediatrician’s office have lactation consultants – people trained to teach women how to breast feed and address problems that come up in the process. I used their help when my son was born two years ago, and I certainly plan to take advantage of them again this time.

Update: Hannah May was born on Saturday afternoon and is currently enjoying the benefits of breastfeeding.