You would have to be living in total isolation not to know that American society is rapidly aging. But how rapidly? What’s happening to life expectancy, economics, health and related issues as our society “greys?”

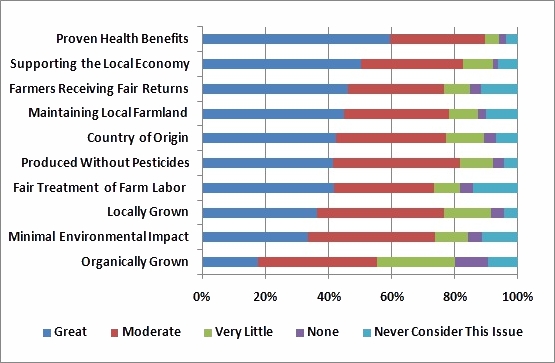

The good news: Today’s older Americans enjoy longer lives and better health than did previous generations. These and other trends are reported in Older Americans 2010: Key Indicators of Well-Being, a unique, comprehensive look at aging in the United States from the Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. This easy-to-understand report provides an updated, accessible compendium of indicators, drawn from the most reliable official statistics about the well-being of Americans primarily age 65 and older. The indicators are categorized into five broad areas—population, economics, health status, health risks and behaviors, and health care. In addition, the site provides very nice Powerpoint slides of all charts.

No matter how old you are now, you are aging, so this information should be of interest to all of us.