I am guessing that many families reading the paper at breakfast today had this happen: Somebody said to someone else: “See, I told you drinking diet soda was bad for you!”

And that is because of a study reported widely in the media regarding the relationship between consumption of diet soda and stroke. Strokes are very bad things, often devastating the person to whom they occur, so a finding about anything that might increase our risk for stroke is worthy of notice.

At Evidence-Based Living, one of the most fun things we do is to track back from the media coverage to the actual research findings. In so doing, we hope to help people figure out the nature of the evidence and whether we should immediately change our behavior. This was an unusually big story, and so we ask: Believe it or not?

First, let me say that media coverage was a little more measured than usual. Some news outlets did use headlines like that from Fox News: “Diet Soda Drinkers at Increased Risk for Stroke” which make it sound like a firm finding (and probably led to some of the heated breakfast-table conversations). But many other outlets included the all-important “may” in the headline, and the articles themselves included qualifications about the study.

So let’s take a look at this finding, using some of the key questions EBL recommends you always employ when you are trying to figure out whether a scientific finding should change the way you live.

1. What kind of a study was this? Was it a good one?

This is what scientists call an observational study. It was not a randomized, controlled experiment in which some people were asked to drink diet soda and others were not. It uses a longitudinal study called the Northern Manhattan study (or NOMAS). And yes, it is a very good study of its kind. It looks at stroke risk factors across white, black, and Hispanic populations living in the same community (northern Manhattan). It is a large and representative sample, followed up annually to determine if people suffered a stroke (verified by doctors on the research team). Many publications in top referred scientific journals have been published from the study (some of which are available for free on the website).

2. Where did the information in the media come from?

Here, in EBL’s opinion, is the first problem. The results were presented at a scientific conference this week (the American Stroke Association). This is not the same as being published in a referred scientific journal. In addition, we cannot follow an EBL cardinal rule: Go to the original article. The only information that is available on the study is from a press release issued by the association and subsequent interviews with the study’s lead author and other experts. So we need to wait until the results are published before we even think of changing our behavior in response to them.

3. Are the results definitive?

No, no, and again no. There are some good reasons not to drink diet soda (including possible increased risk of diabetes and osteoporosis), but these findings do not “prove” that diet soda leads to strokes.

Some reasons why this is a very tentative and preliminary finding include the following:

-

All the data are self-report, so we are dependent on people remembering their diet soda consumption.

-

It’s the first study to show this association. EBL readers know that we need multiple studies before we even begin to think about recommending behavior change.

-

It’s not all diet soda drinking: It looks like only people drinking diet soda every day show the association with stroke, suggesting that lower consumption may not increase risk.

-

The study is not representative of the U. S. population. First of all, you had to be over 39 years old in 1990 to get in the study and the average age of the sample now is in the late 60s, so the results can’t be generalized to younger people. Further, the sample for this study included 63% women, 21 % whites, 24 % blacks and 53 % Hispanics. In the U.S as a whole, 51% of the population are women, 77% are white, 23% black, and 16% Hispanic. So it’s a very different group from what a random sample of Americans would get you.

-

We don’t know the reason for the association. The lead author, Hannah Gardener, is open about this: “It’s reasonable to have doubts, because we don’t have a clear mechanism. This needs to be viewed as a preliminary study,” By “clear mechanism,” she means that even if this relationship exists between diet soda and stroke, we don’t know why.

There’s more we could say, but our main point is this: It doesn’t take very long for you to “deconstruct” what the actual evidence is behind a news story. With a basic understanding of how studies are done and access to the Web, you can often find out as much as you need to know. In this case, the media have reported the first highly tentative findings of an association between two things. Now other scientists need to test it again and again to see if it holds up, as well as finding out why the association exists.

I go for sparkling water instead of diet soda because of other problems mentioned earlier with diet beverages. But regarding stroke risk, the data just aren’t there yet.

I think we should be wary of all substances that are unnatural to life, including artificial sweeteners and other food additives.

This also applies to all sorts of other chemicals found in furniture, toys, etc. We don’t know how these things will affect us in the long run, so in my opinion we should try to minimize them in our environment.

I’m going to start with the myths she’s imposing on you and then get to the causes.

Sugar: She’s diabetic, but she doesn’t really understand what affects blood sugar. Yes, sugary food absolutely raises blood sugar levels in a diabetic. She’s leaving out carbohydrates, though. Sugar is one type of carbohydrate, but carbohydrates like bread or rice also become glucose (sugar) in the blood, and so are a problem for diabetics. She can keep you away from sweets all she wants, but even by her logic – foods that diabetics have to avoid are foods that cause diabetes (untrue) – she’s leaving out most carbohydrates.

Meat: Meat is zero carbohydrate and hardly has any impact on blood sugar because of how slowly it metabolizes. As a Type 2, I eat meat every day. While I like eggs and chicken, I also have pork, red meat (steak, beef), and seafood, too. Meat is actually very healthy for a diabetic to eat, so I am not exactly sure why she’d limit protein. What’s sad is she’s also cutting out the healthiest types of meat. Compared to red meat, chicken offers very little nutrients. Red meat is loaded with iron and zinc. She may think chicken and eggs are “lower fat,” but fat has no impact whatsoever on blood sugar levels and is a diabetic-friendly food. Also, red meat can be just as low fat as chicken or fish or turkey. The cut of the meat matters.

Weight: Let her know that muscle mass is actually really good for diabetics to have. Muscle makes a diabetic a better glucose burner. So if muscles are good for diabetics, why wouldn’t they be good for you? Weight is just a number and doesn’t tell a doctor anything about health except in the very broad strokes. If you gain weight due acquiring a lot of muscle mass, you have not put yourself at greater risk of diabetes. You have gotten healthier and fitter.

All right, as for the causes… well, if there were just one cause, this would be a lot easier. No, being overweight does not cause diabetes. Food does not cause diabetes, sugar or carbohydrates. Being lazy and sedentary does not cause diabetes. These are all myths based either on poor understandings of diabetes or loose correlations. People know that diabetics have high blood SUGAR and limit intake of SUGAR, so maybe they falsely conclude that diabetics ate a buttload of sugar before diagnosis. Nope. Diabetes is an insulin and metabolic problem, so if sugar or carbohydrates raise your blood sugar, you already have diabetes. The sugar/carbohydrates did not cause it. Also, let’s keep in mind that most people in the world eat a very high-carb diet, yet most people never get diabetes. So if food really causes it, why don’t we have MANY more diabetics than we do?

It’s true that most Type 2s are overweight – note: fat, not greater weight due to muscle – when diagnosed. The problem with that statement is that most overweight people in the world are not diabetic. So there’s actually a reverse correlation. People assume that if you’re fat, you’ll get diabetes, but it’s more like, if you’re diabetic, you’re probably fat. Why does this matter? Because if fat causes it, then why aren’t more fat people diabetic? Instead, I think what a lot of researchers now understand is that diabetes is very likely what’s making people fat. Diabetics usually have a lot of metabolic problems, like insulin resistance, in the works many years before diabetes ever happens. These metabolic problems contribute to weight gain. You can still get diabetes without being fat and you can be fat without diabetic, all depending on why you’re fat or why you got diabetes. It’s just that, often, metabolic disorders precede and cause diabetes in Type 2s.

The two biggest risk factors are actually just genes and age. So yes, you may be at increased risk of becoming diabetic. The research is out on whether you can actually prevent this from happening. You may do everything right and still become diabetic. You may eat chips and cookies every day and never become diabetic. If you are suffering from a metabolic disorder and mildly insulin resistant, a diabetic diet (low carbohydrate) may be a good idea, but honestly, who knows. I think a lot of us want to believe diabetes is 100% preventable because it’s more comforting to live in a world where we believe bad things happen to bad people and good things happen to good people, that diseases aren’t random, that we can control our fates to a certain degree. This would make life a lot chaotic and scary and a lot more predictable. And I wish it were true.

I am always wary of any product that is highly processed or that has alot of additives in it, I grew up on a farm so it is kind of instilled in me, the problem is most people haven’t a clue what they put in their bodies nor do they care.

People should be willing to go to the source of information: to the studies themselves. This will give a much clearer picture than getting the refined (distorted) angle from the media. Schools should teach children how to read and analyze research to know what is true and founded and what is not.

The reasons mentioned in this article are not really good enough to disprove the data that was reported about diet drinks and strokes.

First of all, the nature of the problem makes finding the reason for the association a non-issue. Just suspecting a negative result is enough to halt until further notice. The simpsons comic mentioned in another comment is funny, but she was claiming a positive result with no reason for the results. In other words, it is smart to use caution with a possible negative side effect. That’s just a commonly known and used part of science.

Secondly, the self-reported info issue is also a bit more unique in this study. If I asked you how many times a week you drink coffee and you said at least once a day (which is what the results are staking as the general threshold). There is a very low chance that your memory is wrong. You are a habitual coffee drinker. Now, if you are not, then it would be harder to remember and you might inadvertently give

misinformation. But something that a person seeks out daily is not something they are going to remember wrong. They may remember the amount of times during the day, but the results of the test just rested on daily, not how many each day.

Thirdly, just being logical, someone has to be the first to produce the study. So I don’t see how that can really be an issue. Unless there are other studies that disprove these results, it doesn’t really prove or “deconstruct” anything to be the first study. It’s like you’re trying to disprove a scientific study with pure suspicion and no science whatsoever.

Fourthly, The age part is appropriate because the statistics on strokes are that they occur way more often in older people, so the only purpose in starting the study younger would be to figure out what consuming young and then quitting would do to the study. That would be interesting, but that’s a different study all together.

If you had found an issue with the type of test, that would be very scientific and interesting, but you found it to be a good test.

Don’t get me wrong, I like searching back and finding if some data was misinterpreted or skewed or even just totally biased, as many studies are. but the points you make about this particular study do not deconstruct the study’s results.

I think we should be wary of all substances that are unnatural to life, including artificial sweeteners and other food additives.

This also applies to all sorts of other chemicals found in furniture, toys, etc. We don’t know how these things will affect us in the long run, so in my opinion we should try to minimize them in our environment.

Some of them are probably harmless, but I’m sure that time will show us that many of them are indeed harmful.

I kind of skimmed through the study and noticed that the issue wasn’t really soda per se as much as it is sodium intake. The study itself suddenly switches focus from soda and I’ve noticed so do a lot of the news articles about this study — the problem is the damage is already done for the normal reader who doesn’t actually “read” much of anything online.

So if we’re to presume I drank nothing but soda all day and 4000 mg of sodium per day is bad (which from my perspective is really high, but that’s what the articles mention), I’d need to drink 100 cans of this stuff. Factoring in what I eat per day, I’d still have to drink in a ridiculous amount of soda to get near this number.

Looking around news sites that allow comments it seems like no one is actually reading this thing. It’s fun to jump on big companies and I figured this was going to be some huge blow to them, but reading more into it it just all seems really specious.

If this study didn’t look at other history or what else these people do then what can I even draw from it? I’m more likely to have soda at a fast food restaurant and, guess what, their stuff is packed full of sodium. How does that affect this study? Apparently those involved didn’t even want to know.

It reminds me of that Simpons episode where Lisa sells Homer a rock that keeps away tigers. He asks how it works and she says “It doesn’t. But do you see any tigers around?” and he immediately buys it.

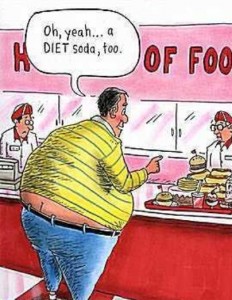

Anyway, the cartoon is funny… Although I always wondered how getting something with less sugar is a bad idea even if you’re eating well or badly. I’d prefer the thing with tons less sugar even if I’m having a burger lol

Hi Tony,

Thanks for your post! I was interested as well that the findings related to salt were buried in every article – and salt is probably a bigger threat. And I think the other point your comments imply is an important one: there could be a third confounding variable that leads to both soda drinking and stroke. I myself drink the occasional diet soda, and there’s nothing here that suggests to me I should stop!

Karl